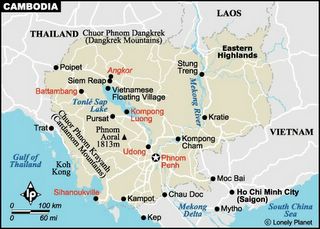

On Wednesday morning last week, at 8:30am, I hit the road again. This time the trip was to Svay Reing province on the Vietnamese border to observe IDE’s new fertilizer pellet and drip irrigation programs. For those of you interested in the finer details of both programs, I’ve included links to the various illustrated summaries I’ve been writing about both of these programs. Don’t worry, it’s simple non-technical stuff interlaced with information about rural livelihoods here in Cambodia.

Drip IrrigationFertilizerOn the subject of rural livelihoods though, I’ve decided to forego the possible stories of driving across dried up rice paddies in a pickup truck, drinking palm-tree juice at the home of a village chief, and eating a still wider variety of strange fruits and insects. (See how I subtly slipped the stories in anyway? ;-)).

Instead, I’m going to share with you what I’ve managed to learn so far about the day-to-day situation of farmers during my visit in Svay Rieng province. As near as I can tell, it’s fairly representative of much of Cambodia. Bearing in mind though, as I’ve only been here two weeks, I suspect that this doesn’t do more than scratch the surface of the situation.

Traditional Hand Mill

Traditional Hand MillSvay Rieng province is undergoing a drought. So is Prey Vang province. In a country that saw mass starvation and genocide under Pol Pot only 25 years ago, this is nothing to write home about. The World Food Programme is beginning to distribute food to pre-empt the problem. This is not uncommon. Here in Cambodia when people ask for more rice while eating, they say “World Food Programme, please,” as a joke.

Cambodia has very poor irrigation infrastructure. Some fields are baked so dry that the ground cracks during the dry season. Others are completely flooded during the rainy season. Though farmers are more than willing to work, their fields may only be usable for one hundred days of the year. The rest of the year they must find another means by which to feed themselves and their family.

The government has recently announced a large push in funding for large-scale irrigation projects. Though in theory, projects to distribute Cambodia’s water resources more effectively could vastly improve the lot of farmers, no one holds out much hope of it happening. Corruption ensures that only a fraction of the money reaches its target. In the meanwhile, the reigning politicians of Cambodia’s nominal democracy pay attention to the rural areas near to election time but otherwise play their own game.

Depending on the size and quality of their crop, farmers may earn as little as $125USD per year. I’ve heard that in the very poor areas, a single family can be fed and maintained on only about $1USD per week. I’m not sure if this is true, but certainly, these people are poor by any definition of the word.

Rice is the primary crop. Some farmers will try to grow vegetables for sale as a cash crop. There is an understanding in villages though that if a neighbour asks for a small part of your vegetable harvest, you give it. Thus the farmers who do farm alternate crops lose much of their work directly to their community. There are also difficulties in getting their produce to market. In tropical heat, food spoils quickly. Many farmers, without a distributor willing to visit them, will peddle their produce by bike for sale in a market several kilometers away. The end result: Fewer farmers growing anything other than rice, and widespread malnutrition.

So, with insufficient funds and land that is useful for only part of the year, many farmers seek to supplement their income elsewhere. In Svay Rieng, one popular option is gas smuggling across the Vietnamese border. Gas prices in Vietnam are significantly lower than in Cambodia. I saw a few motorbikes in my drive through the rice paddies carrying enough gas to defy the laws of physics as they drove in from the other side of the border. Others will seek work in the large cities where manual labour pays about $2.50/day. A girl old enough to work as a seamstress (sweatshop) can earn $3.50/day. A skilled bricklayer might earn $5.00/day. A prostitute can earn $15.00/customer/night. In Phnom Penh, prostitution seems to be an accepted part of male culture. You wouldn’t want your sister/daughter/future wife involved but your friends might call a few girls to come join you for a night of Karaoke.

Morals in the village environment are extremely strict and enforced through a community where everyone knows everyone else’s business. When the fields cannot be used, entire villages will be nearly emptied of all but children and the elderly as the population goes to seek work in the city. As people flood out of the community, this restraining force is gone and many will purchase the services of prostitutes, leading to an increase in STIs upon their return.

In Cambodia, education is free up to the end of high school around age eighteen. Effectively this means that rural children will be educated until they are about eleven before being pulled out to help their families earn a living from the land or from work elsewhere. Social mobility in general can be extremely limited. Between nepotism, corruption, and the difficulty of obtaining an education, it’s not what you know but where you were born, who you’re related to, and which wheels you can afford to grease that will determine your success. Hard work pays but only if the circumstances are right.

Now add in the problem of landmines in some parts of the country where farmers are forced by necessity to work land that has not been properly cleared and you have a real mess. In this country, about 1 in 236 people has lost a limb to a landmine. The social safety net here is virtually non-existent. I’ve heard one man angrily tell me of doctors leaving patients who could not pay for services to die in the street. For those who do survive, depending on the extent of their injury, their ability to work is extremely hampered, leading many to beg.

In addition to all of their other problems, nearly every person in this country over 30 is a survivor of the Khmer Rouge genocide. My neighbour has very limited English. We speak through charades and single words in Khmer and English. The other day I asked him what the Khmer word for father was. He misunderstood and made a chopping motion at his neck. It took me five minutes to understand that he thought I was asking after his father. Realisation dawned when he said “Pol Pot” as he chopped.

All of the above should be taken with a grain of salt of course. I’ve only been here two weeks and thus the amount of information and perspective that I’ve been able to gather is limited. I’m sure there are whole other chunks to these stories of which I know nothing.

That being said, to me the most remarkable thing is how the situation here doesn’t seem grim on a day to day basis. In general, the people are cheerful and conscientious. The rural poor are often dressed in old clothes with holes in them but they are always scrupulous in maintaining a clean home, offering tea and/or food to their guests, and taking a genuine pride in what they do have. Wherever I’ve gone thus far, I’ve been greeted with smiles, friendliness, and in some cases very strange new foods. The local equivalent of the maple tree would seem to be the palm tree. They tap its sap for juice and boil away the juice to make sugar, tasty but with a very odd aftertaste.

I’m sure that’s more than enough for now though. I know that much of this read almost like a cliché from a Sunday morning infomercial. I also know that many of you were curious what the situation is like here and I’ve done my best to explain it as I know it. Basically though, the only think of which I’m certain at this point is that the situation is difficult, it’s unfair, and the people here are far more resilient than a just world would expect of them.

In other news, if/when I get around to it, the next blog entry should include photos of monkeys. ;)

For now, I'll leave you with a photo of one of my coworkers taken in our van on the way back from the field.

Kimsan on the Ride Home

Kimsan on the Ride Home