Cultural Snapshots

Better late than never, after repeated requests from some of you I’ve set up an e-mail list to notify subscribers when the blog is updated. Please send an e-mail to adamincambodia-subscribe@yahoogroups.com to subscribe.

Though it’s impossible to relate the intricacies of an entire culture in a short blog entry, I hope that the items below will give some idea of the subtleties involves in learning one’s way in Khmer society. At the most fundamental level, everything is the same. People love their children, worry about the future, reminisce about the past, and try to find comfort in the present. Much is also the same on the surface. People eat, sleep, work, play games, clean their homes, wash their clothes, and generally go on with the business of life. It’s everything in between that at first defies explanation.

Soccer on the Beach

I still don’t know if it’s poverty or simply a very different set of cultural values that causes it but child nudity is perfectly acceptable in Cambodia until about the age of four or so.

Taken while on a break at the beach in Sihanoukville the weekend before last, if there was a Cambodia’s Funniest Home Videos, I’d be sending it to them. Click on the picture to see the movie.

The Language

Khmer writing has roughly one hundred symbols. One of the greatest joys and challenges I’ve had since coming to Cambodia has been learning how to speak, read, and write in the local language. It’s very different from English. There is no word for you. Addressing someone requires that they be referred to in the third person. There are endless ways of doing this, including ‘little brother’, ‘young miss’, ‘older brother’, ‘older sister’, ‘auntie’, ‘uncle’, ‘great uncle’, ‘great aunt’, ‘mister’, and. ‘madam.’ Foreigners don’t fit anywhere in the social hierarchy so we’re generally just referred to as ‘person.’ If you’re both drunk and angry outside a karaoke bar in the north of Phnom Penh, ‘despicable one’ is also an option.

Though the words for he, she, and they are all the same, there is still a distinction depending on if the person or group needs to be formally respected or is a close acquaintance. There is no verb conjugation. There is also very little distinction between nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, etc. The same word may fill three of these functions at once. For this reason, sentence order is often very important. Consider the words ‘baan’, ‘neung’, and ‘hai-ee’:

| Khmer | English |

|---|---|

| Neung hai-ee. | That’s right. |

| Hai-ee neung. | And |

| K’nyom jong bai hai-ee. | I already wanted rice. |

| K’nyom neung jong bai. | I will want rice. |

| K’nyom baan jong bai. | I wanted rice. |

| K’nyom jong baan bai. | I want to get rice. |

| K’nyom jong bai baan. | I am able to want rice. |

| K’nyom neung jong bai hai-ee baan. | I will have been able to want rice. |

That last one is just a guess…

When speaking, pronunciation is key. The difference between ‘great uncle’ and ‘despicable one’ is the difference between ‘Om’ and ‘Ah.’ Dog, distant, and tasty are ‘ch’gai’, ‘ch’ngai’, and ‘ch’ngain’ respectively. Even more difficult are table, water, and boat: ‘toc’, ‘dteuk’, and ‘touq.’ After these the differences sometimes become too subtle for English writing to convey. Things are especially difficult when riding on a motorcycle taxi since the words for ‘stop’ and ‘quicker’ both sound like ‘cho-op.’

I Call This Little Fellow, “The Gouger”

Living in a completely foreign country with no language skills, even buying simple household supplies becomes a challenge. I purchased this item from the market near my home for a very specific purpose. It took a little figuring out, but eventually, I got it to work. Anyone have any idea what it does and how it works…? Post a comment. First successful guess wins a prize after my return. I’ll post the answer in the comments sometime next week.

Bracelet Making

Two weeks ago, Phalla, the receptionist at IDE, requested that I find her a string bracelet during my trip to Sihanoukville. I spotted a young girl on the beach selling them during my last morning in town. “How much for one?” I called out to her in Khmer. “Two dollars,” she responded in English.

“Whoa! That’s expensive!” I exclaimed in Khmer.

“Not expensive at all!” she rejoined. “Do you know how long it takes to make one of these?!”

“Yes. I know exactly how long it takes. I’ve made many just like it,” I responded.

She and two of her friends were soon testing my bracelet making abilities. After I had proved myself by making a small ring out of six strings, they showed me a variety of stitches, asking which ones I knew how to make. When we found a simple one I had never seen before, they offered to teach it to me. The bracelet-seller held one end of the strings in her hand while I began knotting the others to begin the work on Phalla’s bracelet.

As we sat together in the sun, we began to learn a bit about each other. I asked her if she went to school. “No. I have no time for this,” she replied. Working on her own, this young girl had taught herself English by selling bracelets and beauty treatments to foreign tourists. She used these skills to support herself, her elder sister, and her elder sister’s young child. Though obviously bright, she had no thoughts for her own education. At thirteen years old, the several dollars a day she earned from foreign tourists must have made her richer than most of the adults she knew.

She and her friends told me that I looked like I was from Israel not Canada, commented that the Israeli tourists seemed rude, and asked me if I was a “lady-boy,” the popular term from Thailand for traditional transvestites. “No. I just like making bracelets,” I replied. After a little off-key singing of popular Khmer pop songs, a brief lesson in Hebrew to help them with the next batch of rude Israelis, a few laughs, and a new bracelet for Phalla, it was time for the girls to go back to earning the money that would support their families.

“Can I give you something for your time teaching me or at least for the string?” I called out to her as she left, “Is two thousand riel okay?”

“Ot ai-ee!” she called back kindly but brusquely. Don’t worry about it. I’ll earn more soon enough.

Moto-Drivers

If there’s one thing that’s easy to find in Phnom Penh, it’s someone who wants to give you a lift on his motorbike. You can hardly throw a rock without hitting a motorcycle taxi in this city. Odds are he’ll be pretty surprised when you do. With his hand already raised as he called out to offer you a ride, the rock wasn't necessary to get his attention.

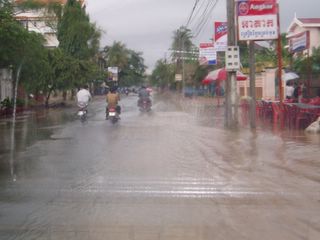

When fields are flooded during the rainy season or cracked and dusty during the dry, those men from the provinces who are lucky enough to own a motorbike often come to Phnom Penh to seek their fortune as taxi drivers. Despite the high demand for their services, there is still a glut of supply that keeps prices very low.

Until recently, my policy when hiring a moto was simply to hand the driver the appropriate fare at the end of the ride. Though prices vary with time of day, distance-traveled, and number of riders, it doesn’t take long to learn the system. When you’ve underpaid, the moto-driver will let you know and politely ask for more. Haggling before the journey, or worse still after it, demonstrates that you don’t know the system and usually results in the price being doubled.

For all of these reasons I was shocked when a few weeks ago, after handing my driver the going fare for a journey home from the market, he demanded that I triple it. We asked a woman manning a nearby phone booth to mediate the dispute. “Going from the new market to here, I say 1000 riel, he says 3000 riel, how much do you think it should cost?” I asked her. A little taken aback at being involved in our affairs, she suggested 1500 riel. The motorcycle driver was having none of it. “2000 riel!” he insisted. “1500 I can do but 2000, I will not,” was my reply.

The standoff continued. Eventually, realising that I was running late for my friend Sunday’s engagement party, I placed the fare on his bike and turned my back to walk away.

“Hey!!” he shouted.

I turned around. The moto-driver grabbed a thick metal chain from off his bike, threatening to hit me with it.

Cambodia is the only nation in this region to tax gas rather than subsidise it. This has made life difficult for the poor in many sectors but soaring gas prices seem to be hitting the moto drivers particularly hard. Given all of this, his actions were understandable. Still, leaving a taxi driver with the impression that threatening foreigners is a good way to earn extra cash is the beginning of a very slippery slope. I stared back at him, inwardly relieved that it was a chain and not a knife that he was holding.

“You are only asking for more because I am a foreigner. This is not good!” I told him emphatically. “Gas is very expensive. You’re not good!” he retorted. Luckily for me, we were in my neighbourhood. Two friends who work across the street soon came looking to see what the problem was. The moto-driver began explaining angrily to them about the cheap foreigner.

My home is near the old brothel district. Making the obvious assumption, I suspect the moto-driver couldn't figure out why all the locals were supporting the strange prostitute-seeking foreigner instead of him. In any event, frustrated and bewildered, with a growing crowd surrounding us, he eventually relented and accepted the 1500 riel fare we had had mediated before.

I certainly shared responsibility for the conflict. I should have haggled the price in advance. As some coworkers later told me, “It’s not about how much is fair. It’s about the expectation.” Poverty is a terrible thing. The 500 riel, which was so important to this man that he felt justified threatening me for it, is worth about 12 US cents.

Fortune Tellers

They burn incense, read cards, look at palms, and are consulted for everything in this country. They seem to fill a role somewhere between marriage counselor, psychologist, and priest. Though I have yet to visit one myself, everyone else from my co-workers to the Prime Minister does. One friend of mine, due to fly out of the country soon, was told, “You should try to be as good and kind as possible or their may be a disaster coming to you soon. I see you possibly falling from a great height.” As she summarised succinctly later, “Be good or else!”

Though it’s recognized that no fortune-teller is always right and that some are more accurate than others, their influence can be very powerful. Sunday, with whom I work closely at IDE, had his marriage dissolve after consulting one. He and his wife were arguing constantly. They spoke to a fortune-teller who told them that for the next year they would be unable to be in the same house without arguing. She advised them to separate for that time. Afterwards, if they chose to do so, they could move back together and continue the marriage. One year later, Sunday’s now ex-wife refuses to let him see or speak to his daughter, who is beginning to forget him,. Instead, he finds himself engaged to a new girl named Monika.

There may be trouble brewing though. During a joint consultation with a fortune-teller, Monika was warned that she should keep a close eye on Sunday as he has a wandering eye. The fortune-teller may have been on to something. Sunday is quite the lady’s man.

In the meantime, they’ve already consulted another fortune-teller to find an auspicious date for the wedding. He’s told them that despite the recent death of a close relative, it should be done in the next ninety days. They plan to consult yet another fortune-teller for a second opinion shortly.

The House Call

In this country, the brightest students all want to learn English. If you want to be one of the few Cambodians lucky enough to have a stable well-paying job, it’s a necessity. To me, it seems painfully unfair. Imagine if employment in Canada required a working knowledge of Khmer.

The practical upshot is that as a foreigner living in Cambodia, people on the street will randomly approach me and try to converse with me to practice their English. Some are ominously eager to establish friendships. I’ve had the following conversation several times:

“Hello, what is your name? Where are you from?”

“Hello. How are you? My name is Adam. I come from Canada.”

“What do you do in Cambodia?”

“I work with an organization in Phnom Penh. I’m an engineer.”

“How long will you stay in Cambodia?”

“A few more months.”

“I would like us to be good friends. What is your phone number? Can I call to you?”

“Okay… This card has my phone number on it. If you call me, maybe you can practice your English with me and I can practice my Khmer with you.”

“Wow! I am so very happy to meet you! Next time when I call to you I would like to see your house.”

For a seasoned traveler, this kind of eagerness to make friends and potentially see where they keep their valuables sets off countless alarm bells. The conversation was repeated so many times though that I eventually asked some Khmer friends about it. As it turns out, in Khmer culture, cementing a friendship involves touring each other’s homes. It helps both parties to know that the other is being honest.

I’ve completed this ritual with four or five different friends. One of them was a high school student in his final year named Whin. The first time he tried to start a conversation with me while biking on a major city street. Given traffic conditions in Phnom Penh, I admired his determination if not his sense of safety.

On our third meeting, we exchanged house visits. He lives with his parents and siblings in a three-room wooden shack in the north of town. They’ve lived there for ten years. Each family member sleeps on a wooden palette covered by a reed mat. Some of the floorboards in the kitchen have completed rotted through to the point where I was warned to be careful where I stepped lest I fall into the swamp below. Whin’s mother is a seamstress and his father a mechanic. Though the home is modest, they’ve done their best to make it nice. Old cigarette ads and strips of linoleum have been used as posters on the wall. The two altars to his father’s and his mother’s ancestors are well maintained, stocked with fresh offerings of bananas and incense. Photographs of relatives past and present reside in frames along the wall.

Whin’s a bright guy. He’s smart enough to have taken the one dollar a day it costs him to attend school and used it to its fullest. He’s hoping to get good exam results so that he can obtain a scholarship for university. Without it, he won’t study again after high school.

Back at my place after visiting his, I introduced him to my new roommate, Greg. Greg’s an MBA graduate from Kellogg in the States, working with IDE for one month to consult on the marketing plan for our fertilizer pellet program. I think they both fascinated each other. Whin with his stories of Cambodian life was a new experience for Greg and Greg with his explanation that WWF Smackdown, a surprisingly popular TV program in this country, is not actually real, was astonishing to Whin.

Cost of Living

I’ve heard that many Cambodian families living in Prey Veng province survive on $100USD per year. I’ve also seen countless rich Phnom Penh residents flashing the latest cell phone and cruising about in private Landrovers that may never venture outside city limits.

Living in Cambodia, I’m painfully aware of just how much more my money is worth here than at home. Working for EWB, I’m also very aware that my income originates with the charitable donations of others. With that in mind, I conducted a bit of an experiment, recording every expenditure I made throughout the month of May. For the activists who clamour for greater transparency amongst charitable organizations, this may be a rare glimpse of what would usually be summarized as “Volunteer Expenditures.”

You can find the resulting budget here. The short version is that 30% of my costs went to rent, 30% to exploring and learning more about the country, and the remaining 40% mostly to food. Bearing in mind that here in Cambodia, there are three long weekends in May, and that I took advantage of every one of them to explore, that first 30% is probably a little disproportionate.