Après la Mort, la Vie Continue

Rwanda is beautiful.

The Country of a Thousand Hillsides – Le Pays des Milles Collines – it gives the impression of a rumpled blanket, covering the fitful sleep of a slow unseen giant. The countryside is a patchwork of sloping banana tree fields and vegetable patches, dropping down into tea plantation valleys. The wispy clouds above are complimented by the green of the tea leaves below, a deep, pleasant, and relaxing colour. It’s almost enough to make one forget the nauseating stop and start of the curves in the road, and the steep unforgiving drop just a short driver’s error away to the left.

Just across the Ugandan border, the road provides its own stern warning: the charred skeleton of a petrol truck, lying at the bottom of a hundred-foot black scar. The smoke has mostly cleared as we drive past.

Rwandan Landscape

Our driver continues obliviously onward, treating the speedometer like a bungee cord as he bounces between sixty and thirty kilometers per hour at every bend. The speedometer is likely broken anyway. It has been my experience that in poor countries, they always are. Exhausted from several days of travel, I curl up in my seat, resigned to whatever fate has in store.

I am in Rwanda at the invitation of my friend Aska, a Polish medical student I met in Cambodia last year. She is on an International Federation of Medical Students exchange at the University of Butare in the south of the country.

Arriving in the capital after a ten hour bus ride I am soon informed that the last bus to Butare has already left. I find an alternative route on public transport. Four hours and several dozen stops later, I saunter into a restaurant in Butare, a dusty mess with a large backpack. Thankfully, Aska is there waiting with friends. She’s already entertained them with the story of how we met, traveling on the roof of a pickup in Cambodia. My ragged entrance seems appropriate.

They invite me to join them at a dance club. Émanuel, a Rwandan medical student in his final year of studies, is warm and friendly. He seems to take a special delight in looking after foreign visitors. As the girls gyrate their way to distant corners of the club, he stays behind to make sure that Laurent, a French student, and I are both comfortable. We’ve both been awkwardly practicing our respective versions of the white man shuffle. Surrounded by the kind of booty-shaking that can only be seen in Africa, our lack of rhythm draws attention.

We are soon joined by other enthusiastic Rwandans, men and women who are happy to offer words of encouragement, "No, no. Don’t worry so much. Relax! Have fun! Just feel the music. … Much better!"

This is Rwanda. At first glance, it is a country beautiful, friendly, and open. Old men pass the time playing Igisoro, a subtly complex game of sixty-four stones in thirty-two piles. Women sidestep around puddles and people, carrying snack trays for sale. Children shout "Bonjour Mzungu!" at passing foreigners. An exception amongst poor countries, the government passes progressive laws, and the people actually follow them. Every motorcyclist wears a helmet. Taxis even carry an extra one for their passengers. Every major road is paved with barely a pothole in sight. Plastic bags have been replaced by environmentally friendly paper ones. In the hospitals, volunteers dressed in pink clean and tend the grounds.

"Il y a un esprit de développement ici." – "There is a feeling of progress here," I told a Rwandan named Émile when he asked what I thought of his country. He had just been telling me about the genocide. Émile is a Tutsi. He survived by moving from one hiding place to the next. Several members of his family weren’t so lucky. "Après la mort, la vie continue" – "After death, life continues," he replied.

That is also Rwanda, a country littered with genocide memorials and mass graves, a country in which only twelve years ago, men, women, and children butchered men, women, and children.

After World War II, European civilians could claim they were unaware of the genocide in their midst. In Rwanda, there is no such option. With the limited resources of a poor country, the Hutu massacred the Tutsi with whatever was ready to hand: machetes, hoes, and clubs. For a hundred days, people murdered from sunrise to sunset, stopping only for food and rest. It was hard work. Those Hutu who refused to help were often massacred alongside the Tutsi. Unable to escape, victims were gathered in groups to watch and await their turn.

The volunteers in pink do not work voluntarily. They are génocidaires, former participants in the genocide. With limited resources and countless accused, Rwanda relies on traditional courts. Every week, businesses close so that the population can convene to hear evidence. The guilty are usually sentenced to public service. It has been twelve years since the genocide ended. The lists of accused are still long.

Génocidaires at the Hospital in Butare

I gave a talk in January at a synagogue, contrasting the Cambodian Genocide with the Jewish Holocaust. "How can you begin to compare such atrocities?" I was asked. Here I didn’t have to. The Kigali Genocide Memorial Museum had already done so, with displays of the mandatory identity cards that labeled Tutsis, the propaganda that dehumanized them, and the tools that killed them.

The Hutu Ten Commandments, a document widely circulated by the Hutu Power movement before the genocide, exhorts all Hutu: "Show no mercy to the Tutsi!" It forbids marrying Tutsi, frequenting Tutsi businesses, or showing kindness even to Tutsi within one’s own family. Substitute Jew for Tutsi and the commandments provide a good summary of the Nuremberg laws of Nazi Germany.

The museum contains displays of other genocides from the Armenians to Nazi Europe, from Cambodia to Yugoslavia. The Children’s Memorial in the basement is a darkened room in which the names of children are recited in an overwhelming seemingly endless list. If it were filled with the lights of flickering candles, it would be a perfect replica of the Children’s Memorial at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. There is even a hallway paying tribute to righteous Hutus who risked their lives to save Tutsi. At its centre is a quote from the Talmud in English, French, and Kinyarwanda, "He who saves one life, it is as if he had saved the world."

There is an eery feeling in the museum, a sense that though we know nearly nothing of the history of these people, they know us and ours well. That feeling is confirmed by a glass plaque in the final display, the museum’s central unspoken message:

"When they said ‘Never again’ after the Holocaust, was it meant for some people and not for others?"

–Apollon Kabahizi

It’s a valid question. While Interahamwe militias manned roadblocks, scouring throughout the country for Tutsi to kill, the United States government actively blocked the United Nations from sending troops to intervene. Until the bodies were piled so high that dump trucks were required to remove them, US officials refused to use the word "genocide." Under international law, that word would have required them to do something to stop it.

France was worse. President Mitterrand was so closely linked to the Hutu Power movement, its leaders referred to him affectionately as Mitterahamwe. Before the genocide, French troops helped in identifying Tutsi. As the genocidal government collapsed, France unilaterally created its own UN mission under the banner of humanitarianism. New French soldiers arrived enthusiastically, expecting to save lives. Many quickly became disillusioned as they provided a safe retreat for fleeing génocidaires.

After publishing One Boy at the start of this month, I was asked, "It’s great to say you should care but practically what action can you take?"

It’s a difficult question. I spent much of my time in Rwanda thinking on it. Here is my answer: Care actively. Become interested enough in the injustices you hear about at home and abroad to learn about them.

We are active in the things we care about. Governments act on the issues of greatest concern to voters. Corporations act on the needs and demands of consumers and shareholders. We are voters, consumers, and shareholders. When we care as much about an injustice as we do about the environment, health care, and gas prices, corporations and governments will take notice.

We want a simple solution, a path that has already been laid for us: Click a link. Sign a petition. Buy a product. The small solutions are good but they don’t absolve us of the need to educate ourselves. Learn. Don’t stop because a practical direction is unclear. The first step is understanding. Solutions won’t immediately follow but the next step will.

Lt. General Romeo Dallaire, a Canadian who led the United Nations Peacekeeping force during the genocide, has said repeatedly that with only four thousand troops he could have ended the slaughter. Subsequent military analysts have agreed with him. No country was willing to send those troops. We in Canada had the resources to help. We chose not to do so. The Belgians, who composed most of the troops in the UN mission, withdrew days after the killings began.

"Riskless warfare in pursuit of human rights is a moral contradiction. The concept of human rights assumes that all human life is of equal value. Risk-free warfare presumes that our lives matter more than those we are intervening to save."

– Michael Ignatieff

Four thousand troops could have saved eight hundred-thousand dead.

I met two Australian UN workers this week. They were on leave in Kampala from Southern Sudan. I asked them about the situation under the current peace agreement.

"Peace agreement?! There’s no peace and no agreement. Most of the groups didn’t sign it. Many of the remaining groups, Janjiweed and others, might as well be working for the government. No worries though. There will be peace in Sudan. It’s coming just as soon as they’ve eliminated or pushed all the undesirables across the border."

"Après la mort, la vie continue."

Unfortunately, neglect, apathy, and genocide do too.

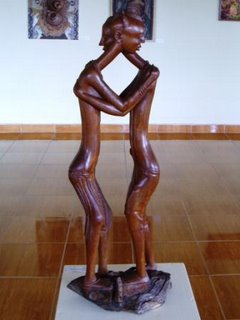

As for the Rwandans, the government while coping with the same problems of poverty faced by its neighbours, has done a miraculous job of keeping both sides living peacefully side by side. Artwork in national galleries more often than not has titles like "Reconciliation," "Peace," "Compassion."

Rwandan Art

The Tutsi still remember the murder of their families. The Hutu still mistrust and fear the Tutsi. Witnesses set to appear before the traditional courts still disappear. So do former génocidaires. Nevertheless, the Rwandans are moving forward. As Émile told me, "Most génocidaires were poor and angry. They were told to kill, coerced to kill, and they killed. They did not know what they were doing. If one of these now understands his actions and wants forgiveness, we must forgive." After all, what alternative is there?

"The only conclusion I can reach is that we are in desperate need of a transfusion of humanity. If we believe that all humans are human, then how are we going to prove it? It can only be proved through our actions. Through the dollars we are prepared to expend to improve conditions in the Third World, through the time and energy we devote to solving devastating problems like AIDS, through the lives of our soldiers, which we are prepared to sacrifice for the sake of humanity."

–Lt. General Romeo Dallaire, Shake Hands with the Devil