Moving Vegetables: Just the Beginning

Below is the final entry from this online journal. It contains a last update from my work on the vegetable packaging and transport project. My apologies for the delay. I’ve been in classes at the University of Toronto Medical School for nearly two weeks now. Life has become very busy very quickly. For anyone wishing to contact me, starting Monday I can be reached at:

69 Ontario St.

Toronto ON

M5A 2V1

(416) 703-4136.

Email: adam dot kaufman at utoronto dot ca

Just replace the ‘dot’s with ‘.’ and the ‘at’ with ‘@’.

Thank you to everyone who offered support, donations, and encouragement during my time in Cambodia. A big thank you also to those of you who helped to disseminate these articles to a larger audience.

There’s a Jewish saying of which a friend of mine is very fond: “Yours is not to complete the work [of repairing the world] but neither is it to shirk from it.” There is a lot of work out there still to be done. There is also a very real power to effect change from here at home.

I remain convinced that the first step in making positive changes in the world around us is through humility and learning. For those who would like to continue to learn and become a little more involved themselves in the kind of work that’s been described here, please click on the links below. Join a workplace campaign. Make a donation. Continue to take a little time on the Internet to learn, disseminate, and encourage others to become a little more socially active.

A small warning though: Knowledge is a two-edged sword. Knowing more means being less able to ignore the problems around you. It means greater responsibility. To borrow from another often quoted Jewish saying: "If not me, who? If not now, when?"

Online Learning

Workplace Campaigns

Getting Involved

Donate to EWB

(If you wish to specify that your funds be allocated specifically to Cambodian work, you must send an e-mail to office@ewb.ca after donating.)

Donate to IDE

(If you wish to specify that your funds be allocated specifically to Cambodian work, please make this request when completing your donation.)

I’ll be giving talks about my work overseas in the coming months. I’ll try to keep this site updated with dates and times as they develop. For now though, please enjoy the last entry.

Moving Vegetables: Just the Beginning

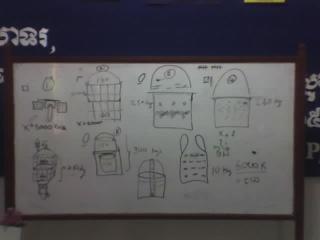

Knowing the countless ways that vegetables are moved about the Cambodian countryside, we had decided to focus on the most popular means of transport: giant one-metre-wide wicker baskets, metal crates, and plastic bags. Collectors moving vegetables from farm to market used the first two. Wholesalers and retailers traveling between markets used the latter one. Sunday, our head of R&D came up with a whole slew of possible designs to counter the excess weight, poor ventilation, and trapped heat and moisture that cause spoilage.

Coming up with an inexpensive way to modify the plastic bags seemed easy. We punched holes in them to increase ventilation. Modifying the baskets and crates was more difficult. We played around with ideas that involved inserting perforated plastic pipes into the baskets to increase ventilation. We tried to find ways to divide one crate into two so as to limit overloading. We even combined ideas, layering the baskets with a combination of plastic pipes and bamboo platforms. In the end though, the most important part of the design process was to consult with the collectors who would actually be using the baskets. Here’s what they told us:

“We don’t care about spoilage. Our problem is that we pay too much for everything: gas, crates, baskets, vegetables. All of it.”

Given our funding was directly tied to reducing spoilage, this was some pretty demoralising news.

One way or the other though, it was also too important to ignore. We asked them for design ideas. We showed them some of ours. We asked them if they’d be willing to pay for a basket that reduced spoilage and therefore decreased some of their costs. In a fairly grudging manner, after making it clear that they would never consider paying more than an extra 5000 Riel ($1.25USD) for it, they voted for the simplest design as the most preferable, a completely ordinary wicker basket with a bamboo platform on the lid to divide the weight of the vegetables in half and provide increased ventilation.

I later learned that Sunday had learned something during our encounter that had completely escaped my attention. A giant wicker basket holding 200kg of vegetables is not a very durable invention. It tends to break after only ten to the market. At 13000 Riel ($3.25USD) per basket, that’s a big expense to someone who quite literally needs to count every penny.

We designed the baskets with extra bamboo reinforcements secured on the outside with metal wires to better support the new platforms. The resulting baskets were so durable that they could hold 400kg for over sixteen hours at a time.

We sent our survey team to the market to begin testing them. The plan was simple. Hire a collector already transporting two baskets to the market. Have that collector transport his or her vegetables using both an old basket and a new basket side by side. Allow retailers purchasing his or her crop at the market to throw away any spoiled vegetables at our expense. Measure the weight of vegetables spoiled in both baskets at the end of the evening. Use some of the vegetables from the baskets to perform similar tests in two sets of plastic bags, some perforated with holes, some not.

It seemed simple enough but this was Cambodia. With a plan that stringent, problems were inevitable. The bamboo made our baskets rigid and hard to manipulate. It poked and scraped the faces of the labourers carrying the baskets. The metal wires poking out of the sides and occasionally gouging them didn’t help matters. Wholesalers were unhappy too. Though we’d paid them a fair rate for their time, we wouldn’t allow them to add water to their vegetables at the market. It would have corrupted our weight measurements.

They also hated the plastic bags. In an effort to make them extra snazzy, Sunday had used a more durable thicker plastic than was normally available. We hadn’t realized that because plastic bags are usually sold by the kilo rather than by the bag, this made them significantly more expensive.

No one was happy. Our survey team spent a sleepless night enduring repeated jibes about their pointless and irritating little experiment that was losing collectors far more money than it was worth. It was painful to watch.

We gave them the following day off to recuperate. It was the least we could do. In the meantime, we rethought our strategy. We rebuilt the baskets. We purchased thinner lighter plastic bags. We placed the bamboo on the inside. We made sure that the metal wires were tied off in a position that would harm neither vegetables nor people. We rebuilt the platforms to be sturdier. We rearranged the entire experiment so as to ease the concerns of the collectors with whom we worked.

We arranged a new meeting with the surveyors to discuss the changes. All seemed to be going swimmingly until I asked the inevitable final question: “Does anyone have any other questions or comments?”

A hand was hesitantly raised. A question of procedure was haltingly asked. It was answered. Another hand was raised, another question asked. Things rapidly went from halting to enthusiastic. The floodgates had been opened. Question after question, concern after concern, criticism after criticism came flooding down upon us. Sunday frantically translated for over an hour as we adapted our plans to the rapidly growing list of concerns.

But it didn’t end. As soon as one concern was addressed, another would be raised. Though Sunday seemed blissfully unaware of it, I soon noticed a recurring pattern. We’d been stuck for an hour addressing the same three problems in an endless loop. I was not in my best form. My project seemed to be crashing for no explicable reason and I was becoming both frustrated and angry. I turned to Sunday and asked him to translate for me for me word for word.

“I’ve noticed we really just seem to have three problems here…” I began.

- Wholesalers will refuse not to add water to freshen their vegetables during sale.

- Retailers purchasing the vegetables don’t care if they’re spoiled or not so they can’t be relied on to separate out spoiled vegetables.

- There’s simply not enough room in a crowded market to be constantly checking the plastic bags for spoiled vegetables

“My Khmer is horrible and I know I’m missing a lot, but are there any other problems being raised…?” I asked.

“Well, the markets are very crowded and I just don’t see how…”

“Problem 3,” I interrupted.

“Not to mention there was this wholesaler who was very angry about the weight he lost from not adding water…”

“Problem 1,” I interrupted again.

A blissful silence filled the room. Linear logic applied in this manner is not part of Cambodian culture. No one was prepared for it. Even Sunday seemed taken by surprise. Everyone sat in a sort of stunned silence as I confidently continued, “With respect to retailers not finding spoiled vegetables,” I continued, “Since the retailers are the ones who define what is or is not sellable, if they don’t think a vegetable is spoiled, for our purposes, it’s not spoiled. This means that there is no problem 2.”

Some surprised murmurs occurred before head-nodding and silence again filled the room.

“With respect to not having room to make measurements,” I once again began, “there are lulls in the market. Don’t worry about making measurements regularly. Just make them when the crowds thin a bit.”

“We can’t do that!” one surveyor cried out.

“Why not?” I inquired, smiling manically, as is customary in Cambodia when one is about to explode with frustration.

“The wholesalers wouldn’t be comfortable with it. They don’t want us getting in their way,” was the enigmatic reply.

“I’m sorry…” I responded, “I’m failing to understand… if you do it at a time when no one is around, there will be plenty of room. You won’t be in their way. Where’s the problem?”

The conversation again went in circles until finally one surveyor forcefully declared, “Even if they’re comfortable with it, we wouldn’t be!”

I now understood what had happened. The surveyors were unwilling to say it, it would have shamed them to do so, but they understandably wanted nothing to do with another failed experiment. To avoid that shame, they were instead trying to dodge the problem by raising enough roadblocks to make it hopefully disappear on its own. I, with my dirty foreigner logic tricks, had nearly ruined this plan. We were at an impasse. The meeting was adjourned.

It was mid-July. I had only one month remaining to my time in Cambodia. The project was already running late. Sunday, Kimsan, and I stayed very late that day, trying to find a solution. Having rebuilt the prototypes, we now needed to rebuild the whole experiment again.

Working overtime that night, we eventually found a solution that was both workable and affordable. Starting the next week we sent three of our surveyors to work alongside a single collector by the name of Koom Chanee. We gained her permission to purchase vegetables from farmers with whom she already had agreements to buy.

Since we owned the vegetables, we could dictate what was done with them. We asked the surveyors to sell them once they’d completed their measurements. They refused point blank. They felt that as literate employees, selling vegetables in a market was beneath their station. This was another cultural roadblock that in my ignorance I had not anticipated. Nevertheless, this one at least was easily overcome. At the end of the night, Koom Chanee made use of her connections to sell off all of the remaining vegetables, giving half the revenue to us and keeping the remainder for herself.

Our collector was overjoyed. She was earning three to five times her normal income. We were overjoyed. Our measurements were reliable and easily obtained. Our budget was not overjoyed. It could only afford to subsidise ten trials before disappearing.

Luckily ten trials were all that was needed to gain results that were nothing short of remarkable. Our new modified baskets cut spoilage in half. The bags cut it down even farther. While an ordinary basket would have been useless after ten trips, I recently received an e-mail telling me that ours are still going strong after 20.

In the meantime, the remaining two surveyors were sent off to distribute prototype baskets amongst collectors working in the area. After using the prototype baskets for between two and three days, their opinions were collected. The collectors loved them. They all wanted to be able to purchase their own. The unusual design of the modified baskets even seemed to attract curious customers at market who later stayed to buy more vegetables.

We took two days to run a blind Pepsi Challenge type test in the market asking people to compare the quality of unspoiled vegetables from both kinds of basket. 75% of people instinctively by look, feel, and smell could tell that the vegetables from the new baskets were better.

By the time the survey ended, word about the new wonder-baskets had spread amongst collectors. Simply because a friend had told them about it, people were able to anticipate their benefits without ever having seen one. For those of you interested in the finer points, the final project report can be found here.

As things stood just before my return home, AQIP, was planning to begin refining and manufacturing these baskets on a wider scale, increasing consumer exposure to them and creating a demand for them that could easily be filled by one or several entrepreneurs. I've since heard that IDE has again be contracted to work on this project on their behalf. There are still many challenges to be overcome. It will be years at best before this project can be said with complete certainty to be a success. Nevertheless, right now, it’s looking very good indeed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home