Hill Tribes of Ratanakiri

One week later and I’m back in Phnom Penh. The trip was one new experience after another. I departed early Saturday morning on a small minibus from Phnom Penh to Kratie, a province a little to the north of Phnom Penh. An overnight trip by pickup truck on Sunday brought me to Ratanakiri, one of Cambodia’s most remote provinces where, I’m happy to report, I was greeted by the sight of countless billboards advertising the Cambodian Red Cross’ Ceramic Water Purifier, a product manufactured at a factory for whose establishment my EWB predecessor, Selena, was responsible. I hope my work here is half as successful.

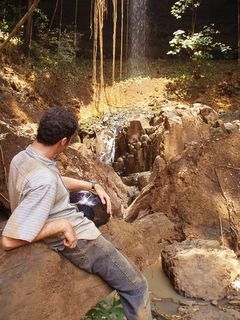

With a week’s worth of backlogged e-mails, a couple of projects back on the go at IDE, and a belly full of the lemon tofu stir fry sandwich I just ate for dinner, I can’t muster up the energy to write all of my stories just now. I do promise, however, that I’ll post the highlights, pictures included, retroactively over the next few weeks. The picture below was taken at the Cha Ong waterfall gorge, about 5km outside of Ban Lung in Ratanakiri.

In the meanwhile, I’d like to try a bit of an experiment. Working here is continually changing and shaping my perspective on development. With more time to think and plenty to ponder, my views on poverty, education, gender equality, nepotism, corruption, the role of technology, the role of NGOs, and especially my own role as a development worker here in Cambodia have been constantly in flux. Many of you will probably already have seen this in my e-mails home. Thinking is fun but less productive alone. I’d like to be able to share some of this process with others. This is where the experiment begins.

During EWB volunteer training we focused a lot of time on analyzing the cycle of poverty. Poverty has many causes. Each cause has many effects. Some of these effects may cause other problems that lead to greater poverty. It’s a hard cycle to break. I’m going to try to focus on one or two of these causes/effects and explain the problem. There is no single good solution to any of them, only options and ideas. I’d like to see if I can get a discussion going in the comments section of the blog. This is my attempt to share with you some of what I’m learning here in between posts about the life and culture here. I’d also love to see what others thing.

This time, in keeping with the Ratanakiri theme, I’m going to talk a bit about the problem of development versus indigenous rights. Ratanakiri is home to Cambodia’s hill tribe minorities, known collectively as the Khmer Loeu. There are a variety of tribes, including the Tampuon, Chunchiet, and Krung, each living in their own villages with their own tools and traditions. In post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia, their livelihoods were upset for many years by Cambodia’s illegal timber trade. Corrupt members of the government and military, including both Prime Ministers would award massive illegal logging contracts to the highest bidder. They were quite brazen about it. Land used and occupied by these tribes would be appropriated, exploited, and left. Villagers who attempted to interfere were turned away at gunpoint by army personnel brought in by generals who were also involved in the scam.

Eventually, through the effort of several NGOs, the Khmer Loeu were educated regarding their rights to the land and their legal rights and abilities to fight this problem. Through a combination of well-timed pressure from international environmental groups and their own efforts, they were largely successful. Logging is no longer a major problem in Ratanakiri. In the meanwhile, however, other landowners have been busily purchasing land that once used by the Khmer Loeu, driving them further into the jungle. To sustain their rice farming, they have begun a campaign of slash and burn agriculture. At the end of the dry season, the they now light massive forest fires to clear land so that they will have fields to cultivate during the rainy season. On my visit to Ratanakiri province, I lost count of the number of burned and/or burning fields that I passed. They were everywhere.

This is especially unfortunate since, thanks to years of massive sustained illegal logging, Cambodia is nearing a crisis point in its deforestation. The fields cleared in the jungle are good for maybe three years before they become uselessly depleted of nutrients. In the meanwhile, as the dust in the ground gradually turns former forestland into a desert, the waterways are choked by sand. One government group, I believe it’s called the (

National Timberwood Authority (NTA), is attempting to educate the hill tribes regarding the devastating results of this practice. Still, the Khmer Loeu need a means by which to eat and the NTA does not seem to have provided one yet.

Some would argue that they should take modern jobs. These are unfortunately already in short supply in Cambodia. The increased interaction with modern Cambodia has also begun to erode their traditional way of life. Already they wear modern clothes. I met a Tampuon working for the NGO, Care, in Ratanakiri. He was involved in educational and retraining programs for the tribes in and around Ban Lung, the capital of Ratanakiri. He was also working on an illustrated Tampuon-Kreung-Khmer dictionary. Seeing their culture gradually erode, programs have begun to increase communication and help them preserve it. Still, there is some tension between Khmer and Khmer Loeu. The only time I have heard of Cambodians not making an effort to smile at each other occurs here. A Khmer Loeu will almost never smile at a Khmer.

Cambodian roads are the worst in South East Asia and may be some of the worst on Earth. A trip of 100km can be a six hour journey through craters, across bumpy tracks surrounded by sixty centimeter deep crevasses, and over hills that more closely resemble sand dunes during the dry season and swampland during the rainy. Miraculously for Cambodia, despite the ubiquitous government corruption that has until now hampered all such efforts, the roads in and out of Ratanakiri are beginning to be repaired. With improved roads, a massive influx of businesses and tourists is starting to begin. Already the Internet, albeit slowly and intermittently, has reached Ban Lung. The number of guesthouses seems to have roughly doubled since my Lonely Planet guidebook was published two years ago. The benefits of improved roads are many: better access to health care, ease of transportation for food, increased business across the Laotian border. In other words, as the roads continue to improve there will be an overall improvement in the standard of living of most Khmer in Ratanakiri. Unfortunately, the already endangered Khmer Loeu way of life will be under greater threat.

Reducing their culture to a tourist attraction may help the Khmer Loeu financially but will hardly be of lasting cultural value to them. Retreat from encroaching modernism no longer seems like a viable option either. Slash and burn agriculture is proving a stop gap solution at best to their food needs and in a country starved for firewood, it also seems very wasteful. So, what action should be taken? What is the role of the government? Of NGOs? How is this affected by government corruption? I’ve got some ideas on the subject but I’d love to hear yours. Click on the comment link just below and let me know what you think. Cheers.

3 Comments:

Ah Sarah... I should have remembered you've been studying cultural anthropology recently. ;) Your questions about community reactions and planning are good ones. I wish I knew the answers. I don't know nearly enough. Much of my response below is unresearched speculation based on half-remembered conversations.

I would say that while cultural adaptation is a necessity, what we are seeing here is the growing prospect of the cultural annihilation of a less powerful group by a larger more powerful one. That's aggression no matter how you slice it. I think this, combined with Cambodia's recent history, goes a long way to explaining the animosity the Khmer Loeu feel towards the Khmer.

Primary education is underway and NGOs, including CARE, have launched education and skills training programs. Tourism in the Lake Yeak Lom area, Ratanakiri's most famous landmark, has been designed to support local tribes without too greatly impacting their way of living.

Though I'm not certain, from what I can tell, farming techniques and access to credit are less of a problem than is unethical land appropriation by other groups, driving the Khmer Loeu constantly to find new land.

I think a means needs to be developed to help them decide for themselves how and to what extent they wish to integrate. Acquiring these 'skills' will of necessity accelerate the process of cultural erosion. They will be able to adapt but the cost may still be assimilation, albeit more comfortable assimilation. Simply forcing 'skills training' upon them so that they can 'adapt' looks to me like a polite route to cultural annihilation. Unfortunately, I also suspect that the pace of development may already be so rapid as to make this inevitable.

Dear Adam, I admire your hopes for these people. I have worked in hill tribe areas since 1968 in Thailand and Laos. I studied the impact of highways on the environment. But in all of this we should not use the word logging as a problem. Commerical logging can be stopped overnights when there is a will. But the real problem in Cambodia and other countries along the Tropics is that there are millions of farmers eeking a living through slash and burn. Hundred thousand farmers in Cambodia are destroying the forest, now they are so desparate that they even go ahead of the loggers, and cut down the precious forest, the bigger the more ashes and burn.

So your thoughts should be directed towards finding solution for these hungry farmers, and find an alternative livelihood. The hectarage of destruction of the forest in Cambodia by peasants is now worse than by the loggers.

Slash and burn can be permanent, and only in Cambodia have I seen the perfect sample of sustainable slash and burn. So perfect is the pattern that it is a clasic that even a draftman cannot replica it. So, there is hope and that is to teach the farmers to use rotational swidden. It is being used by a group of farmers, and so it can be done and is being done. It is also being done without the help of anybody. That is what I think and I will visit them and see who taught them this method, and maybe develop an TCDC program (technical Coorperation amond Developing Countries. Good Luck.

Dear Hadi,

Thank you for your kind words and still more for your insight into this problem. When I traveled in Ratanakiri, I frequently saw large tracts of forest land that had been destroyed by slash and burn. I confess that I don’t know how sustainable the Cambodian method is in comparison with others but in general, slash and burn is certainly a cause for concern as those using the practice are constantly being driven further and further into forest areas. If you have the opportunity, there is a book called “There You Go!”, a short insightful comedic portrayal of many of the problems of indigenous people faced with ‘development’. Check out http://www.hungrymanbooks.com. The book is sponsored by Survival International, who I believe have a fair bit of experience in the field. I'm much obliged to you for your input. Good luck in your work!

Adam

Post a Comment

<< Home